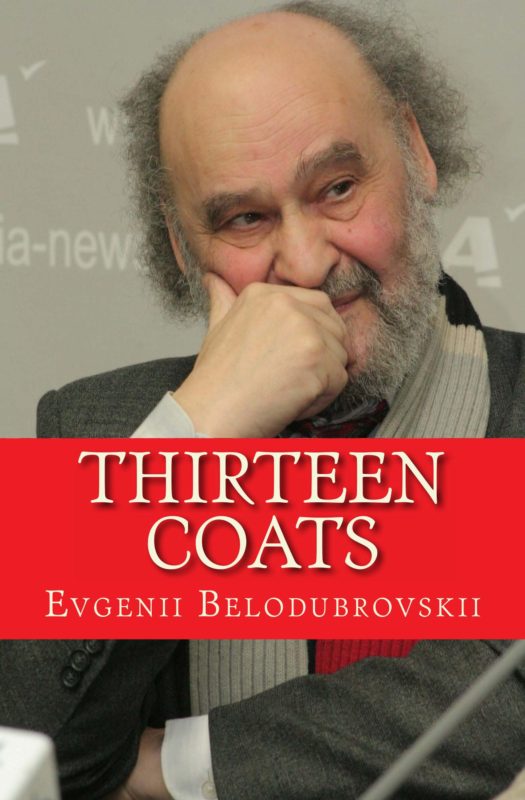

California Zephyr, Grand Junction, Co, 19 October 2012, with author

July 4, 1962

Union Pacific train station, Grand Junction, Colorado

Heat-twisted rails halted the California Zephyr at Grand Junction, Colorado. While the engineer and stationmaster inspected the track west, deciding whether to call a crew to repair the heat rippled track, passengers got off to smoke and stretch legs, remaining under the station overhang against the heat. The station thermometer needle was either buried at 115 degrees or broken. To the northwest was the weather-ravaged face of the mesa, hot white in the sun. Across the street pawnshops and taverns. Beer cans and whiskey bottles were strewn about the street. The white-orange sunlight scalded the concrete buildings white, the asphalt black faded to bruised grey. A discarded newspaper quivered in a non-existant breeze. Had there been a single tree, surely it could only have burst into flame.

Rick knelt in the shade of the station overhang, opened his backpack and withdrew his money envelope from the bottom, counting it––Four one-hundred dollar travellers checks and around $80.00 in cash plus change. It would last him three months until he healed and the Army took him. He withdrew five dollars, put it in his wallet, which he placed in his front pocket against pickpockets. He fingered his traveler’s checks and train ticket. Folded within, a cream-colored sheet of writing paper––M.J.’s concert music program, a piece each of Chopin and Bach, two by Schubert.

Frank lived outside Sacramento somewhere. He would stay with him. Rick had sent a postcard without expecting a reply, would just show up.

The train ticket had cost too much. He could have hitchhiked or caught a freight, but in a few months living paycheck to paycheck would be in the past. He had his plan. There had to be a ball diamond near by. He’d throw, work out the bruise, be ready to pitch by spring. He’d appear at the Sacramento, California Army recruiting office for in-processing, then onto Fort Ord for basic training, then to Fort Sheridan, Illinois, to play U.S. Army intra-division baseball. Army teams played games against major league teams and sometimes won. Famous scouts watched. The medical care was free. They fed and housed you. One needed a plan. Ricky hoisted his pack, a baseball bat stuck out through the flap, glove and spikes hung over the bat. He was for all the world to see an itinerant baseball player.

He paused as his eyes grew accustomed to the dim terminal interior. Dismal. Peeling and yellowed train schedules were taped to walls between advertisements for chewing tobacco. Decades of boots had worn pathways in the dirty green marble floor; beneath the benches the layers of dust remained undisturbed. A few men of indeterminate race, cowboy hats tipped over eyes, napped in heat-induced somnolence.

A ten-stool short-order counter stood at the far end of the terminal. The counter woman, fat with painted eyebrows, watched him. His entrance was the day’s entertainment. Rick pulled his shirt off from his sweating chest, the air-conditioned train a distant memory. A lifetime ago in another train station in another time, a prostitute with a matchbook had careened him south. In the south, a broken bat single careened him west. He had come to heal. He enlisted ahead of the draft. Control. He controlled his fate.

He turned the music program over. M.J. had penned a note. ‘Please call?‘ There was a number. His loneliness deepened. A gust of hot air blew a swirl of dust into the terminal and across the station floor. Two images juxtaposed: She walked across the hay field in overalla and checkered shirt, her hair in a scarf tied at the nape of the neck; she sat at grand piano, a diamond post in her ear wearing long black dress. He smiled.

He should have called. On the wall hung two pay phones. He inserted his dime.

“How much to call this number in Quebec, Canada.”

“Let me check. $4.95 for three minutes; $.75 for each additional minute.”

“That’s steep.”

$1.95 if you call after 7PM; $.25 a minute thereafter.”

He counted his money. $38.00 and some change. He could skip a couple meals until he found a job in Sacramento. A jar of peanut butter at $.79 could be a day’s meal. “I need to get change. Should I call back or let the phone dangle?”

The cashier, cheeks rouged, eyebrows shaven and painted, dark hairs sprouting on her upper lip, crabbed. “I don’t have change for a ten. Go to the drugstore down the block.”

“Trains leaving in a few minutes. I got to call my girl. It’s her birthday. Need quarters, at least five bucks.”

The cashier looked both ways, sighed heavily, and said, “you bums will get me fired yet. Don’t tell anyone I did this for you.”

“Should I buy a coke?”

“Just get out of my sight.”

“Thanks for the change.”

“You getting smart with me?”

” I wish I was smart enough.”

“G’wan.”

He inserted the quarters, listened to the click of relays, sensed the rings echoing down the long dormitory corridor.

The voice announced, “Train leaving in five!”

He heard the female voice. “Allo?”

“Hello, can I speak to M.J.?”

“Comment?”

“Do you speak English?”

“Non, non, pas d’anglais.”

The receiver crackled as if the telephone were struggling to cross border and language, the connection a long thread of spider web strung 2000 miles that could break at a breath of air. “You wouldn’t speak Serbian?” he said in stupid desperation before he switched to his rudimentary French, speaking slowly, enunciating each word. “Je veux parler avec Marie Jeanne Charbonneau. C’est son ami, the American.”

There was laughter on the line. “Elle en a beaucoup, n’est-ce pas?” He neither understood that phrase nor the cascade of words that followed. Sweat came to his forehead as he tried to catch words he might know out of the waterfall.

The terminal had emptied. From the track side of the station came the sound of the release of air brakes. “Mon amie, s’il vous plait, le train depart,” he said, searching for a phrase that she would understand, and then blurted “Tell her that I love her.”

“Don’t they all?” replied the young woman in clear English.

The change dropped into the box. The line went dead. The train moved slowly past the window gaining speed. He looked around the terminal. His pack was gone.