To Conquer the World: A Strategy

I. The Soviet Seven Year Plan (1959-1965)

On March 24, 1953, Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union since 1924, died in Moscow. His  family, followers and state were as children of a powerful, violent and capricious drunk: grief stricken, angry, disoriented, and plotting the inheritance. In his memoirs Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev describes the distemper of the time:

family, followers and state were as children of a powerful, violent and capricious drunk: grief stricken, angry, disoriented, and plotting the inheritance. In his memoirs Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev describes the distemper of the time:

As I recall those days today on June 1, 1971, I am obliged to state honestly that what we inherited after Stalin’s death was painful and difficult. Out country was in disarray. Its leadership, which had taken shape under Stalin, was not a good one… Ten million people were in prison camps…In the international situation there was no light at the end of the tunnel; the Cold War was in full swing. The burden on the people from the priority given to war productions was unbelievable.[1]

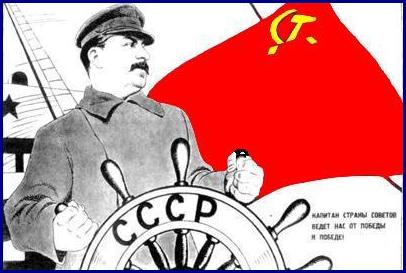

Khrushchev, by 1956 victor in the struggle to succeed Stalin, was a lying, wiley fox with a clear core belief:[2] The struggle between capitalism and communism was to the death; and Marxism-Leninism would emerge victorious. It was inevitable.

In the six years between the death of Stalin and publication of the Soviet Seven Year Plan, Khrushchev had crises to overcome––leadership, doctrinal, domestic and foreign affairs and a gargantuan “man-, money- and metal-eating” military––before the Soviet Union could “go over to the offensive.” The Soviet Seven Year Plan 1959-1965 marked the ‘going over to the offensive,’ articulating a wide-ranging grand strategy to preserve the Soviet Union and gain the victory of Communism in the world.

I examine Khrushchev’s Seven-Year Plan with more than academic interest. In February 1959 I was a twelve-year old peasant child on a dairy farm along a northern Wisconsin single lane dirt road. My parents made little money, but many children. All that brutally cold winter and never again, the aurora borealis hung stationary overhead. In the spring the oozing frost made the road impassable. We carted the milk (hand-milked) to the paved road to intercept the milk truck. One knew that the Communists took away your land and your cows (Saturday Evening Post?). We knew about collectivization (Life Magazine?), slavery no different from than for which my Confederate great-grandfathers died for in Alabama. The Seven Year Plan would soon enough send me with hundreds of thousands of American farm and small-town boys into uniform and around the world; tens of thousands of us to be killed or wounded. Some few of us were privileged to plan and implement the counter-strategy, which defeated the Soviet Seven Year Plan.

I examine Khrushchev’s Seven-Year Plan with more than academic interest. In February 1959 I was a twelve-year old peasant child on a dairy farm along a northern Wisconsin single lane dirt road. My parents made little money, but many children. All that brutally cold winter and never again, the aurora borealis hung stationary overhead. In the spring the oozing frost made the road impassable. We carted the milk (hand-milked) to the paved road to intercept the milk truck. One knew that the Communists took away your land and your cows (Saturday Evening Post?). We knew about collectivization (Life Magazine?), slavery no different from than for which my Confederate great-grandfathers died for in Alabama. The Seven Year Plan would soon enough send me with hundreds of thousands of American farm and small-town boys into uniform and around the world; tens of thousands of us to be killed or wounded. Some few of us were privileged to plan and implement the counter-strategy, which defeated the Soviet Seven Year Plan.

Words have meaning.

II. The Origin of the Soviet Seven Year Plan (1959-1965)

Leadership Crisis

Before the Soviet Union could formulate the strategy to achieve its goal––all mankind living in a state of Communist bliss––a country in disarray needed to be put in order. Who would lead? Stalin’s survivors were Stalin’s children; before Stalin’s body cooled, the leadership struggle commenced.

“As soon as Stalin dies, Beria immediately got into his car and rushed off to Moscow from the “nearby dacha”… I considered him capable of anything, a butcher and murderer who would make short work of those he didn’t like.”[3]

Triumvirates ruled the Soviet Union for three years until by 1956 only Khrushchev remained standing. [4]

Doctrinal Crisis

However, until the doctrinal crisis was resolved, Nikita S. Khrushchev’s would be unable to formulate much less implement the activist, wide-ranging strategy required to achieve Communism’s doctrinal goal. Doctrine is a belief or set of beliefs held and taught by a church, political party, or other group. Communist doctrine (Marxism) taught that Socialism was irreconcilable with Capitalism and the former inevitably overcomes the latter. Soviet Communist doctrine (Marxism-Leninism) posited further that Russia was the cradle of the revolution, from whence this eventual victory of Communism over Capitalism derives. In his 1902 pamphlet, What is to be Done? Lenin wrote:

“History now puts before us an immediate task which is the most revolutionary of all the immediate tasks of the proletariat of any other country. The carrying out of this task the destruction of the most powerful support not only for European but also (we may now say) Asiatic reaction would make the Russian proletariat the vanguard of the international revolutionary proletariat.” [5]

By this Lenin meant that the Russian proletariat, by overthrowing Russian autocracy would open the path to proletarian revolution in the West. Western commentators repeatedly, early and late, noted the messianic strain in Lenin’s Communism. Stanley Page in a 1950ˆ Slavic and East European Studies article noted:

The adherence to it, however irrationally, on the part of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, provided a kind of world mission and supplied them with tremendous motivating energy… It further left an important heritage in Bolshevik thinking; the concept of the centralistic importance to world revolution of the Russian proletariat. To this, by degrees, has been added the notion that Russia must export, rather than merely inspire, world revolution.[6]

This doctrinal foundation––the inevitable victory of Communism, its course either this way or that, its duration either sooner or later, stated either as profound belief or boilerplate––was the first paragraph of all Soviet documents great and small from the early to the last days of Communism. Each Soviet (and Sovietologist) was as a matter of course expected to be:

… a close reader of Communist texts,… one of the best ways available to fathom what was going on in the minds of those at the top of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. The speeches and ‘toasts’ were prepared with utmost care… In the Kremlin, each sentence was numbered, and within each sentence the numbering sequence was refined. In this way “86.4” would take you directly to the point in question, should some member of the Politburo raise an issue of doctrine. All this was necessary in a culture where commissars and cadres–and Kremlinologists and Dragonologists–would scrutinize each text with the intensity of medieval scholastics searching for signs of ultimate meaning. [7]

Woe unto him who did not cite doctrine, chapter and verse to advance his plan. When in 1953 Lavrentij Beria proposed to abandon Socialism in East Germany, i.e. propose the abandonment of Communist workers,.[8] Khrushchev was able to charge him with doctrinal heresy and execute him.

a. Stalin: Marxist and/or Mass Murderer

In 1955 N. S. Khrushchev stood atop the Kremlin wall, a convinced Marxist-Leninist.[9] But before this Communist true believer could march off leading the proletariat to the eventual and inevitable victory of Communism, one burning question had to be answered. Was Stalinism Marxism-Leninism?

By 1928 Stalin had consolidated his rule. For 35 years the peoples of the Soviet Union endured mass murder, war, imprisonment, death by starvation, ruled through a perverted trust that only functioned through the use or threat of terror. Estimates of unnatural deaths in the Soviet Union through the breadth of Stalin’s rule range from 35-65 million.[10] Was this the future Khrushchev would wish upon the children of the earth? Before Communism could resume progress on its messianic mission, there would be a last victim of Stalin’s purges, which would take place before the Twentieth Party Congress in January-February 1956.

b. The Twentieth Party Congress

On 26 February 1956, Khrushchev squared the circle: Stalin was a good Communist who murdered hundreds of thousands of Communists and millions of Russians. Why did Khrushchev purge Stalin? We have his own voluble recollection and interpretation;[11] Sergey, Khrushchev’s son, takes his father at his word[12], expanding upon his father’s recollection with footnotes. Roy Medvedev, conscious of the danger Khrushchev courted and recognizing the Russian peasant beating his chest, listened with sympathetic skepticism, judging Khrushchev’s “truth” by the “feel”[13]. Douglas Crankshaw[14] and other Western historians knew the Soviet Premier was a voluble, enthusiastic and inveterate liar, whose each and every word must first be verified. Medvedev thought that Khrushchev himself probably would not have been able to give a satisfactory answer, and notes the predominate explanations: First, it is suggested, he wished to lift the burden of terror off the nomenklatura that they become more effective in implementing his proposed reforms; second, the 20th Congress was a decisive episode in his power struggle against those even closer to Stalin––Molotov, Kaganovich, Malenkov, Voroshilov and Mikoyan––who might have considered that they were more suitable than he, both politically and morally, to succeed to the power of the late despot; third, that as Solzhenitsyn postulates, this was not a political calculation, but a ‘moment of the heart.’ There yet remained 10 million Russians in the Gulag; each and every Soviet citizen, Khrushchev included, was personally connected to one or more prisoners still dying in Magadan or Norilsk; fourth, the calculation that the unspeakable truth of Stalin’s murderous regime, which Khrushchev himself equated with Hitler’s, would get out sooner or later; if the Communist Party of the Soviet Union released this truth; it could manage the truth. The crisis could be overcome step-by-step.

Khrushchev, being Khrushchev, credited them all.[15]. In the end, Khrushchev regretfully burned Stalin at the stake on the collected works of Lenin and Marx before an open-mouthed mass of Communist aristocrats: Stalin was not a true Marxist, but a mass murderer.[16]

Communist Doctrine has been patched, if not repaired. Stalin, the usurper, the False Dmitrii, has been purged. Leninism is true. Russia was the cradle of Communism, messianic with global reach. The prison camps have been closed. The leadership is now one––Khrushchev––which had foresworn terror.

International Crisis

When Stalin died, his perception of a weakened Soviet Union surrounded by rearming enemies was true, however much this was of his own making. Brutal Soviet behavior in Eastern Europe allowed US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to ring the Soviet Union with military alliances. The European Recovery Plan (The Marshall Plan) unleashed dynamic and growing West European economies placing indigenous Communist parties on the political defensive. A crisis proportion East to West population movements was underway. Relations with Red China were at best correct and cold. Yugoslavia had split with the Soviet Union. Relations with Britain, France and Japan were bad and with the United States even worse. The Cold War was in full frost causing the misallocation of scare Soviet resources.

Meanwhile our country had reached the limit of its endurance because of the unending capital investments in defense. Our military industry had expanded greatly in depth and extent. The army, with its huge numbers of people, was a heavy weight on the budget. It cost us enormous material resources. Vast human resources were diverted, which might have been used to develop a peacetime economy.[17]

After Stalin’s death the Soviet Union’s new leadership instituted a series of radical changes in the country’s foreign policy. The Korean War was brought to an end. Protracted negotiations brought peace to French Indo-China. The Soviet Union extended large credits to the People’s Republic and signed a series of technical agreements. After prolonged negotiations Austria was declared an independent and permanently neutral country. In July 1955 Khrushchev (with Bulganin and Zhukov) attended the first meeting since 1945 of leaders of the Potsdam four powers (Eisenhower and Dulles (US), McMillan and Eden (England) and Faure and Pinay (France)). The Soviet Union undertook a charm offensive into the third world. As the decade approached its end, the Soviet Union had broken out of self-imposed isolation.

The Soviet leadership, tested, experienced, frontoviki of the Great Fatherland War, now judged the time propitious to create a grand strategy ‘to go over to the offense’ and bring about the Communist paradise in which they devoutly believed. But first there were three conception problems to work through.

Conundrum: Victory in the Nuclear Age

The international correlation of forces was not much changed. The Soviet Union remained weaker––military, economically, politically––by orders of magnitude relative to its ‘main enemy’ the United States alone, much less against any combination of the various alliances arrayed against it. In addition, the existence of nuclear weapons checked Soviet preponderance in conventional military groupings, its single advantageous force correlation.

Thus in 1958 a strategic conundrum stood: If Communist Doctrine brooked no contradiction to its ultimate goal––victory––but nuclear war promised that “‘the survivors would envy the dead,” whither the strategy? This was the conundrum which those formulating a Soviet grand strategy in the Seven Year Plan. Would nuclear weapons, if used, mark the end of mankind or merely the end of the less prepared?

a. Correlation of Forces

The correlation of world forces has changed fundamentally in favor of socialism and to the detriment of capitalism. [18]

General Yevdokim Yeogovich Mal`Tsev (1974)

The Soviet concept of the correlation of world forces provided the Soviet strategic planner the intellectual contrivance with which to continue the conflict below the nuclear threshold. It was a crucial determinate in strategy formulation, since it was considered the determinant of world development. It had been the main concern of Soviet politicians, military men, and researchers, which they worked out over time in great conceptual detail. In the late 1950s the Soviet concept had a decidedly military bent, and could be compared to the Bismarkian concept of balance of power without serious misunderstanding. Over time its meaning returned to its Leninist foundation to include all factors of state power arising from many sources––industrial production, labor discipline, alliances, morale, level of education, etc. Elastic in meaning, correlation of forces was an intuitive concept, too difficult to quantify, but like balance of power, if it shifted against you, it inspired political discomfort in the leadership. Flexible though it might be overall, the Soviet concept contained only one – but certainly very important predetermined point: the final victory of socialism on a world scale. [19]

b. Peaceful Coexistence

Peaceful coexistence in Soviet parlance is a struggle that differs from war not in objectives sought but in the means used. In the words of the late Marshal Boris M. Shaposhnikov of the Red Army, “If war is a continuation of politics only by other means, so also peace is a continuation of conflict by other means.” Peace became the absence of general nuclear war and nothing more. Khrushchev described to his comrades what peaceful coexistence would do:

Peaceful coexistence affords favorable opportunities for the struggle of the working class in the capitalist countries and facilitates the struggle of the peoples of the colonial and dependent countries for their liberation.[20]

A ‘war called peace’ describes peaceful coexistence, a term fraught with implications of Orwellian newspeak that “war is peace” or, more to the point, “peace is war.” The Soviet mirovzreniye may thus be stated briefly: (1) the world is divided into two eternally antagonistic systems that are bound to try to dominate one another; (2) Communism will prevail in the end; and (3) in this struggle all methods are permissible except those that involve a risk of general nuclear war. This was the core meaning of peaceful coexistence.

c. Wars of National Liberation

On January 6, 1961, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev delivered a speech[21] in Moscow in which he predicted that the world was moving toward socialism and that “wars of national liberation” were the main instrument of that movement. He pledged Soviet support for indigenous rebellions to overthrow fascists and capitalists.

Kennedy’s concern to confront guerrilla warfare has frequently been viewed as a response to Nikita Khrushchev’s rhetorical support for “wars of liberation.” Khrushchev’s January 1961 speech, just after Kennedy’s Inauguration, is considered particularly crucial in galvanizing the new president into a program of action). Khrushchev’s rhetoric, however, was probably less important than the current concern over troubles with communists in Laos and in Vietnam, ideological doubts regarding African decolonization, and unfinished business in Cuba-where efforts were underway to slap down the first successful communist revolution in America’s “backyard.”

III. Grand Strategy[22]: The Seven Year Plan

Strategy Formulation

Beware of Greeks bearing gifts[23]. The Greek-Trojan War and its resolution through deception––The Trojan Horse––is known to all. Few understand that the tale is a resolution of a long running dispute between Achilles, the strong warrior, and Ulysses, the man of twists and turns, over grand strategy. Upon the death of Achilles under the arrow of Paris, the correlation of forces has shifted decidedly against the Greeks. They will never overcome Troy by force of arms. The weakened Greeks must seek a winning grand strategy to overcome the Trojans or abandon the war.[24] The weaker party, the Greeks, choose as their strategy guile rather than force. After a ten-year siege, the Greeks seem to abandon their positions, departing on their ships and leaving an enormous wooden horse, an apparently gift, upon the shore. The stolid Trojans debate its significance. Some among them suspect ruse, but fail to convince and, hope victorious over reason, the wishful thinkers breach the wall bringing within the wily Greeks.

Nikita Khrushchev, either the intellectual grand master with “the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function” (F. Scott Fitzgerald) or the confidence man who could speak from both sides of his mouth, often spoke with deep personal feeling of war’s horror, then in the next breath thunder threats across the oceans[25]. In the documents adopted during the Twentieth Party Congress (1956), the thesis of the inevitability of a new world war resulting from “aggressive encroachment of imperialism” was replaced by the thesis of durable ‘peaceful coexistence between different social systems, but speaking on 24 June 1957 Mikoyan at Khrushchev’s prompting:

We were strong enough to keep troops in Hungary and to warn the imperialists that, if they would not stop the war in Egypt, it might come to the use of missile armaments from our side. All acknowledge that with this we decided the fate of Egypt.[26]

In the struggle of the weaker with the stronger, be he an infantry platoon leader[27] or a leader of state, the weaker party must of necessity considers stratagem as a component of their strategy.

So too with the Russians. Stalin is dead; that paysan ruse Nikita Sergeevich now rules. In the Seven Year Plan The Soviet Union, much the weaker party, incorporates stratagem into their strategy for victory. The Soviet leader would pretend tough in the international arena incorporating bluff until correlation of forces aligns to their advantage.

The Seven Year Plan

In September 1958 the Central Committee decided to convene and Extraordinary Twenty-First Congress to discuss the Directives for the new (Seven Year) plan for the development of the economy. Henceforth the plan would define targets for the different branches of the economy.

The main tasks in the Soviet Union in the period from 1959 to 1965 will be the all-round establishment of the material and technical foundation of communism, the further strengthening of the economic and defense might of the USSR and, at the same time, the increasingly full satisfaction of the material and spiritual requirements of the Soviet people. This will be the decisive state in the competition with the capitalist world, when the historic task of overtaking and surpassing the most highly developed capitalist countries in production per head of the population will be carried out. [28]

The economic plan was approved during the January 1959 Extraordinary Congress ( 27 January- 5 February 1959). It was a heady, exciting moment in the march of Communism. All too soon though the component annexes of the plan began failing,[29] some sooner, others enduring to the end.

a. Gosplan

To belabor the obvious, the Soviet Union was organized to achieve its goals through a centrally planned economy. Upon the collapse of War Communism, Gosplan was created by a Decree of the Council of People’s Commissars on 22 February 1921[30]. Khrushchev’s Gosplan evolved over time to function roughly thus by the 1950s:

The Central Committee of the CPSU (more specifically, its Politburo) set basic guidelines for planning, determining the general direction of the economy via control figures (preliminary plan targets), major investment projects (capacity creation), and general economic policies.

The Council of Ministers elaborated on Politburo plan targets and sent them to Gosplan, which gathered data on plan fulfillment.

Gosplan worked out, through trial and error, a set of preliminary plan targets. The planning apparatus alone was a vast organizational arrangement consisting of councils, commissions, governmental officials, specialists, etc. charged with executing and monitoring economic policy.

When Gosplan established the planning goals, economic ministries drafted plans within their jurisdictions and disseminated planning data to the subordinate enterprises. The planning data were sent downward through the planning hierarchy for progressively more detailed elaboration. The ministry received its control targets, which were then disaggregated by branches within the ministry, then by lower units, eventually until each enterprise received its own control figures (production targets).

After this bargaining process, Gosplan received the revised estimates and re-aggregated them as it saw fit. Then, the redrafted plan was sent to the Council of Ministers and the Party’s Politburo and Central Committee Secretariat for approval.

That this central planning was inefficient, ineffective and recognized as such from Khrushchev to the #16 trolleybus driver was clear. Among many who excoriated the system.

Victor Glushkov, the head of the Soviet program of research in cybernetics, estimated recently (1960) “that, failing a radical reform in planning methods, the planning bureaucracy would grow 36-fold by 1980, requiring the services of the entire Soviet population. Such warnings are not exactly novel. Some forty years ago, the dying Lenin wrote: “Vital work we do is sinking in a dead sea of paperwork. We get sucked in by a foul bureaucratic swamp.” [31]

b. The Economic Plan

In Mid-November 1958 Khrushchev publishes the draft of his Seven Year Plan of the Soviet economy in the years 1959-1965. The plan replaces the Sixth Five Year Plan, which was intended to cover the years 1955-60 but attempts at revision proved impossible and it scrapped in 1957 when it became obvious of the objectives for 1960 could not be reached. Khrushchev describes the next seven years as a decisive stage in the competition with the capitalist world and claims that the USSR will have overtaken the UK and West Germany in output per head in 1965.[32]

The main problems considered were those of the country’s economic development in the coming seven years. The control figures given in Khrushchev’s report were most impressive. It was proposed to increase gross industrial production by 80%. engineering production by 100 per cent, the output of electric power by 120 percent and that of the chemical industry by 300 per cent. High rates of development were planned for electronics, electrical engineering, the production of polymer materials and atomic-power engineering. The share of oil and gas in the country’s fuel and power balance was to increase from 31 to 51 percent, and all branches of light industry were to expand, particularly consumer durables such as television sets, refrigerators, and washing machines. Real incomes of workers and collective farmers were to rise by 40 per cent. Fifteen million flats were to be built in the towns and 7 million houses in the villages.[33]

There was a cascade of Western intrigued as well as skeptical commentary. The Soviet propaganda machine went wild.

c. The Military Plan

In 1959, with the publication of Seven Year USSR Defense Plan (1959-1965), The Soviet Union undertook a commitment not only to deter, but also to prevail in a thermonuclear war. This commitment, which ultimately contributed to nation’s fiscal ruin and spiritual collapse three decades later, started with authority and high hopes. The Soviet body politic, small, compact and like-minded, move determinedly to achieve a war-winning military capability.

Harriet Fast Scott in her introduction to V.D. Sokolovskiy. Soviet Military Strategy. Third Edition,[34] reported

Beginning in 1960, top secret writings call a “Special Collection of Articles” began to be published in the classified journal Military Thought. The “Special Collection” contained a discussion of the problems of future war and the new Soviet military doctrine, which had been outlined by Khrushchev at the IV Session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on January 14, 1960. Beginning in 1960, top secret writings call a “Special Collection of Articles” began to be published in the classified journal Military Thought. The “Special Collection” contained a discussion of the problems of future war and the new Soviet military doctrine, which had been outlined by Khrushchev at the IV Session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on January 14, 1960.

The Soviet leadership was clearly aware that in the struggle to achieve superiority over ones likely enemies, success could be attained not only by building weapons of better quality and greater quantity, but also by influencing his opponent to build fewer weapons of lesser quality. In 1957-59 the Soviet Union could not afford both gums and butter. To the extent the Soviet Union could influence the United States to restrain its weapons procurement, so was it better positioned to achieve the objectives of the Seven-Year Defense Plan.

d. The Seven-Year Defense Plan

The Seven Year USSR Defense Plan (1959-1965)[35] was the military annex to the overall USSR Seven Year Plan[36]. According to the Seven Year Defense Plan, the USSR would prevail through a strategy of preemptive defense of the motherland; simultaneous nuclear-rocket strikes would be launched upon several hundred enemy command centers and nuclear-missile sites. With the enemy thus stripped of his nuclear arms, massive conventional formations would secure the peace by occupying the enemy’s territory.Based on their WWII experience, the Soviet planners conceptualized thermonuclear war and developed their strategy from this vision. Leonid I. Brezhnev, then a Secretary of the Central Committee, reportedly presided over this reformulation of defense strategy,and relied upon the advice of his commanding officer from World War II, Lt. Gen A. I. Gastilovich of the General Staff Academy. In 1958-59, according to a published history, Twenty Five Years of the General Staff Academy, work done at that institution led to a revolution in military strategy, with formal adoption of a program by the General Staff in 1959. Upon adoption of The Seven Year Defense Plan, Soviet planning procedures call for tasking of subordinate and lateral echelons to write implementing plans. The KGB was a lateral organization so tasked.

f. The Deception Plan

The KGB, under newly appointed Chief A.N. Shelepin undertook to create a security plan, which would defend the new military strategy from western countermeasures. Alexander N. Shelepin ushered in the modern era of Soviet deception. Through his friendship with Brezhnev and a series of well-received proposals on assigning the KGB a more active role in foreign affairs, Shelepin became KGB chairman in December 1958. At a conference of senior KGB officers in Moscow May 1959, Shelepin addressed the “new” political tasks assigned to the organization. Among the more important were (1) the identification of the United States as the “Main Enemy” (Glavny Protivnik); (2) the notion that Soviet bloc security and intelligence services would cooperate to influence international relations and KGB operatives among the Soviet intelligentsia would be directed against foreigners. Anatoly Golitsyn, an early Soviet intelligence operative who defected in 1961, was the original source on the conference and reported that a significant KGB task was as follows:[37]

The Security and Intelligence services of the whole bloc were to be mobilized to influence international relations in directions required by the new long-range policy, and, in effect, to destabilize the “main enemies’ and weaken the alliances among them.

The newly established disinformation department was to work closely with all other relevant departments in the party and government apparatus throughout the country. To this end, all ministries of the Soviet Union and all first secretaries of republican and provincial party organizations were to be a acquainted with the new political tasks of the KGB to enable them to give support and help where needed.

IV. Grand Strategy Undone

On 15 October 1964 Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev was ousted and succeeded by the triumvirate of Kosygin, Brezhnev and Suslov. The Seven Year Economic Plan had already been scrapped, [38] but the chaotic trajectories set in the Seven Year Plan continued with only tinkered change until Gorbachev’s too late reforms. Doctrine–the victory of socialism–remained unchanged, the military and the KGB expanded, but the economy collapsed.

Gosplan

The Soviet planning process went stagnant. For the duration of the Soviet Union, Gosplan changed not at all. Various bureaucratic fixed throughout the duration of the Soviet Union suffered from the fundamental clotting of ineffective information processing which made the Soviet Union vulnerable to US refusal to supply advanced technologies.[39]

An influential group of conservatives among the Soviet planning executives and economists, while agreeing that the present system of planning does not work satisfactorily, attribute its failures to insufficient detail of information received and orders issued by the planners… The centralizers have a ready answer: high speed electronic computers would do the job.[40]

Of the many reforms proposed, for example, Liberman Thesis of 1959 suggested managers be given greater independence on the grounds that they were in the best position to know what the demand was for particular goods and how to supply that need and was rejected as being ideologically unacceptable.

Doctrine

When during the Carter administration the Soviet leadership calculated America was under weak and fickle leadership, the Soviet Union went on the march IAW Marxist-Leninist doctrine, launching the invasion of Afghanistan, stepping up its adventurous and militaristic foreign policy in the Horn of Africa and middle Africa and accelerating several strategic weapons programs.

Military

In 1976 and working independently in the complex and arcane field of Soviet economic statistics, William T. Lee then at the Stanford Research Institute published an exception to the CIA’s conservative estimate of Soviet National Security Expenditures (NSE). He was able to argue, ultimately convincingly, from Soviet data31 that Soviet spending on defense since 1958 was clearly twice what CIA had estimated, imposed a tremendous burden on that society, but was a sacrifice the Soviet leadership for some reason was willing to make. William Lee’s argument was aided by the fact that CIA had shortly before, based on fortuitously provided classified data, doubled its estimate of Soviet NSE for 1970-1974. So although the “corrected” CIA data for 1970-74 was approximately correct, Lee developed a strong case that the methodology was hopelessly flawed and would never produce data relevant to estimating the comparative burdens of defense on the respective economies.[41]

Stratagem

Soviet deception planners could not have been totally dissatisfied when the Shelepin Deception Plan 1959 unraveled in the waning years of the 1970s. Sir John C. Masterman[42], the author of the classified history of the British program Double-Cross, felt the Abwehr was close to breaking the British stratagem in 1944, only five years after the British deception began. A strong case can be made that for twenty years, the Soviet Union was able to encourage in the minds of key US decision makers the spiral model of international relations and denigrate the deterrence model. Eventually, however Lenin’s original admonition, “Tell them what they want to hear,” could no longer bear the contradiction between the Soviet declaratory vice actual grand strategy.

“Fall, 1961” by Robert Lowell

Back and forth, back and forth

goes the tock, tock, tock

of the orange, bland, ambassadorial

face of the moon

on the grandfather clock.

All autumn, the chafe and jar

of nuclear war;

we have talked our extinction to death.

I swim like a minnow

behind my studio window.

Our end drifts nearer,

the moon lifts,

radiant with terror.

The state

is a diver under a glass bell. …”

Works Cited

Andrew, Christopher M., and Oleg Gordievsky. KGB : The Inside Story of its Foreign Operations from Lenin to Gorbachev. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1990. Print.

Barros, James, and Richard Gregor. Double Deception : Stalin, Hitler, and the Invasion of Russia. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1995. Print.

Beschloss, Michael R. The Crisis Years : Kennedy and Khrushchev, 1960-1963. 1st ed. New York, NY: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991. Print.

Courtois, Stéphane, and Mark Kramer. The Black Book of Communism : Crimes, Terror, Repression. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999. Print.

Dyadkin, Iosif G. Unnatural Deaths in the USSR, 1928-1954. New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1983. Print.

“Foundation of Gosplan, 1921 “Web. 4/14/2011 <http://www.uea.ac.uk/his/webcours/russia/documents/gosplan1.shtml>.

Golitsyn, Anatoliy. New Lies for Old : The Communist Strategy of Deception and Disinformation. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1984. Print.

Haslett, A. W. Soviet Seven Year Plan : 1959-1965. 1st ed. London: Todd Reference Books, 1959. Print.

Hill, Charles. Grand Strategies : Literature, Statecraft, and World Order. New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010. Print.

Hoeffding, Oleg. “Substance and Shadow in the Soviet Seven Year Plan.JSTOR: .” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 37.No. 3 (1959): 394-406. Print.

Karpuk, Paul A. “Reconstructing Gogol”s Project to Write a History of Ukraine.” Canadian Slavonic Papers 51.4 (2009): 413-47. Print.

Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich, and Edward Crankshaw. Khrushchev Remembers. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1970. Print.

Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich, and Sergeĭ Khrushchev. Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University, 2004. Print.

Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich, and Strobe Talbott. Khrushchev Remembers; the Last Testament. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974. Print.

Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich, ed. O nat·s·ional´no-osvoboditel´nom Dvizhenii : (Iz Vystuplenii 1956-1963 Gg.) / N. S. Khrushchev. (1956-1963 ··.). Moskva: Moskva : Izd-vo literatury na inostrannykh i·a·zykakh, 1963. Print.

Khrushchev, Sergei, and William Taubman. Khrushchev on Khrushchev : An Inside Account of the Man and His Era. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. Print.

Lee, William Thomas. The Estimation of Soviet Defense Expenditures, 1955-75 : An Unconventional Approach. New York: Praeger, 1977. Print.

Lenin, Vladimir I. “What Is To Be Done?”Web. 4/14/2011 <http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/>.

Masterman, J. C. The Double-Cross System in the War of 1939 to 1945. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1972. Print.

Medvedev, Roy Aleksandrovich. Khrushchev. Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1982. Print.

Nove, Alec. The Soviet Seven Year Plan; a Study of Economic Progress and Potential in the U. S. S. R. London: Phoenix House, 1960. Print.

Page, Stanley W. “The Russian Proletariat and World Revolution: Lenin’s Views to 1914.” American Slavic and East European Review 10.1 (1951): 1-13. Print.

Penʹkovskiĭ, Oleg Vladimirovich, Frank Gibney, and Edward Crankshaw. The Penkovskiy Papers. 1st ed. London: Collins, 1965. Print.

Rummel, R. J. “DEATH BY GOVERNMENT: GENOCIDE AND MASS MURDER.”Web. 4/15/2011 <http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/NOTE1.HTM>.

Scammel, Michael. “The Price of an Idea.”Web. 4/15/2011 <http://blockyourid.com/~gbpprorg/obama/scammell122099.html>.

Smirnov, Yuri, and V. M. Zubok. “Nuclear Weapons After Stalin’s Death: Moscow Enters the H-Bomb Age.” Cold War International History Project.4 (1994): 1. Print.

Smolinski, Leon. “WHAT NEXT IN SOVIET PLANNING? Foreign Affairs; Jul64, Vol. 42 Issue 4, p602-613, 12pDocument.” Foreign Affairs 42.4 (1964): 602-12. Print.

Sokolovskiĭ, Vasiliĭ Danilovich. Soviet Military Strategy. 3d ed. New York: Crane, Russak, 1975. Print.

Sorley, Lewis. A Better War : The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam. 1st ed. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1999. Print.

[1] Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev and Sergeĭ Khrushchev. Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University, 2004. Print.

[2] Definition of terms. What are those core beliefs, those ideas which constrain an actor’s course of action and which we call sometimes name ideology and at other times doctrine, from which arise strategies to achieve goals.

doctrine, noun.1. what is taught as the belief of a church, a nation, or a group of persons; belief; principle.

ideology, noun, pl. -gies.

1. a set of doctrines or body of opinions that people have.

2. the combined doctrines, assertions, and intentions of a social or political movement.

strategy: to mean a plan of action or policy designed to achieve a major or overall aim : time to develop a coherent economic strategy

[3] Sergei Khrushchev and William Taubman. Khrushchev on Khrushchev : an inside account of the man and his era. Boston: Little, Brown, 1990. Print.

[4] [The first (13 March 1953 – 26 June 1953) consisted of Beria (Arrested July 1953; executed in December), Molotov and Malenkov; the second (until February 1955) of Malenkov, Bulganin and Khrushchev, and third; Khrushchev, Bulganin and Zhukov]. For the best short summary seeRoy Aleksandrovich Medvedev. Khrushchev. Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1982. Print. .

[5] What Is To Be Done?, , 4/14/2011 2011 <http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/>.

[6] Stanley W. Page. “The Russian Proletariat and World Revolution: Lenin’s Views to 1914.” American Slavic and East European Review 10.1 (1951): 1-13. Print.

[7] Charles Hill. Grand strategies : literature, statecraft, and world order. New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010. Print.

[8] Khrushchev and Khrushchev. , Oleg Hoeffding. “Substance and shadow in the Soviet seven year plan.JSTOR: .” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 37.No. 3 (1959): 394-406. Print.(When in 1989 Gorbachev did indeed abandon Socialism in East Germany, Communism in Central and Eastern Europe collapsed)

[9] Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev and Edward Crankshaw. Khrushchev remembers. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1970. Print. , Paul A. Karpuk. “Reconstructing Gogol”s Project to Write a History of Ukraine.” Canadian Slavonic Papers 51.4 (2009): 413-47. Print. Until his death he would assert “Even despite Stalin’s perversions of Lenin’s positions and directives, Marxist-Leninist theory is still the most progressive doctrine in the world. It has enriched, fortified, and armed our people, and it has given us the strength to achieve what we have.”

[10] Stéphane Courtois and Mark Kramer. The black book of communism : crimes, terror, repression. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999. Print. Iosif G. Dyadkin. Unnatural deaths in the USSR, 1928-1954. New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1983. Print. The Price of an Idea, , 4/15/2011 2011 <http://blockyourid.com/~gbpprorg/obama/scammell122099.html>. DEATH BY GOVERNMENT: GENOCIDE AND MASS MURDER, Transaction Publishers, 1994., 4/15/2011 2011 <http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/NOTE1.HTM>. The demographic methodology for counting up genocide is arcane and unsettled, which results in wide disparities.

[11] Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev and Strobe Talbott. Khrushchev remembers; the last testament. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974. Print.

[12] Khrushchev and Khrushchev.

[13] Medvedev.

[14] Khrushchev and Crankshaw.

[15] Ibid. 201-221

[16] Khrushchev to the end held complicated feelings about Stalin; Mass murderer yes, but he did much to advance Communism.

[17] Khrushchev and Khrushchev.

[18] 1. Yevdokim Yegorovich Mal’tsev, “Leninist Concepts of the Defense of Socialism,” Strategic Review, Winter 1975: 99.

[21] Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev, ed. O nat·s·ional´no-osvoboditel´nom dvizhenii : (iz vystuplenii 1956-1963 gg.) / N. S. Khrushchev. (1956-1963 ··.). Moskva: Moskva : Izd-vo literatury na inostrannykh i·a·zykakh, 1963. Print. National liberation-anti-imperialism and Soviet support thereto was a constant rhetorical theme in 60 or so speeches and comments spread over the course of several years are contained in this little collection published in Moscow before his forced retirement.

[23] It is recorded in Virgil’s Aeneid, Book 2, 19 BC: “Do not trust the horse, Trojans. Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks even when they bring gifts.”

[24] I am indebted the Charles Hill for this interpretation. Hill. , James Barros and Richard Gregor. Double deception : Stalin, Hitler, and the invasion of Russia. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1995. Print.

[25] Michael R. Beschloss. The crisis years : Kennedy and Khrushchev, 1960-1963. 1st ed. New York, NY: Edward Burlingame Books, 1991. Print. Theodor Bundy recalled the late. summer and fall of 1961 as “a time of sustained and draining anxiety…there was hardly a week….in which there were not nagging questions about what would happen if…or what one or another or our allies would or would not support, or whether morale in West Berlin itself was holding up.” When he later read Robert Lowell’s poem “Fall 1961”, he felt it captured in own emotions:

All Autumn, the chafe and jar

of nuclear war;

[26] istoricheskii arkhiv 4 (1993) 36 cited in Yuri Smirnov and V. M. Zubok. “Nuclear Weapons after Stalin’s Death: Moscow Enters the H-Bomb Age.” Cold War International History Project.4 (1994): 17. Print.

[27] If your attack is going really well, it’s an ambush; The enemy diversion you are ignoring is the main attack. Murphy’s Laws of Combat (anon)

[28] A. W. Haslett. Soviet seven year plan : 1959-1965. 1st ed. London: Todd Reference Books, 1959. Print. Press release issued by the Soviet Embassy in London dated, Friday, November 14, 1958, under the title ‘Target of Seven-year Plan of Development of National Economy of USSR–Theses of N.S. Khrushchov’s Report to twenty-first Congress of Communist Party of Soviet Union.

[29] Medvedev in Khrushchev, p. 161. In December 1959 the agenda of a regular Central Committee plenum provided for discussion of ‘the further development of agriculture’. Reports were given by the leaders of all the Union Republics. Khrushchev began his own report with a section headed ‘ What the example set by the working people of Ryazan oblast teaches us.’ The point was that just before the plenum opened the Ryazan leader had announced that his oblast had fulfilled all its obligations and had sold the state 150,000 tonnes of meat. They had even undertaken to increase the amount available for procurement to between 180,000 and 200,000 tonnes the next year….It turned out that the success of Ryazan oblast had been a deception. A considerable proportion of the breeding stock and many of the milch cows had been dispatched to meat-packing factories, and collective farmers had been obliged to purchase cattle from neighboring oblasts the following year. Many were ruined. The oblast could not hope to fulfill even its obligations under the Seven-Year Plan, let along more ambitious target. When he realized that his ruse had been uncovered, the First Secretary of the obkom, A. N. Larionov, shot himself.

[30] Foundation of Gosplan, 1921 , , 4/14/2011 2011 <http://www.uea.ac.uk/his/webcours/russia/documents/gosplan1.shtml>.

[31] Leon Smolinski. “WHAT NEXT IN SOVIET PLANNING? Foreign Affairs; Jul64, Vol. 42 Issue 4, p602-613, 12pDocument.” Foreign Affairs 42.4 (1964): 602-12. Print.

[32] Alec Nove. The Soviet seven year plan; a study of economic progress and potential in the U. S. S. R. London: Phoenix House, 1960. Print.

[33] Medvedev.

[34] Vasiliĭ Danilovich Sokolovskiĭ. Soviet military strategy. 3d ed. New York: Crane, Russak, 1975. Print.

[35] Oleg Vladimirovich Penʹkovskiĭ, Frank Gibney, and Edward Crankshaw. The Penkovskiy papers. 1st ed. London: Collins, 1965. Print. Penkovskii passed the documents composing the “Special Collection” of the journal Military Thought, to the West. His hand-written summaries were published after he was executed. Their impact in the West was strongly ameliorated by two factors: First they were think pieces and it was unclear if they would be eventually translated into hardware; and second Soviet counterintelligence was able to strongly encourage the idea among Western journalist of all political persuasion that the Penkovski Papers were a CIA creation. Post-collapse of the Soviet Union, Penkovskii was real. Counter-intelligence is one tricky business.

[36] This is an assertion. I have always thought it a given, but to date I have no documentation. Always another footnote to run down.

[37] Anatoliy Golitsyn. New lies for old : the Communist strategy of deception and disinformation. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1984. Print. See also Christopher M. Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky. KGB : the inside story of its foreign operations from Lenin to Gorbachev. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1990. Print.

[38] Smolinski. Khrushchev’s vitriolic attacks on Gosplan’s methods, the far- reaching administrative reorganization of the economy following the November 1962 Plenum, the virtual scrapping of the Seven Year Plan in June 1963 and the enactment of the new Two Year Plan—all have dramatized the extent of the malfunctioning of the economy and the top leadership’s recognition of the need for reform. What, then, has been prescribed to cure the ailment?

[39] I remember 1982-84 bull sessions at the Pentagon with old Republican grandees guffawing about clotting Commerce Department liscensing procedures for the sale of various restricted products including advanced computer for Gosplan. I will dig up the documentation next draft.

[40] Smolinski.

[41] William Thomas Lee. The estimation of Soviet defense expenditures, 1955-75 : an unconventional approach. New York: Praeger, 1977. Print. , Lewis Sorley. A better war : the unexamined victories and final tragedy of America’s last years in Vietnam. 1st ed. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1999. Print. .. He notes that “In sum, the conventional wisdom of the CIA and SRI estimates has been, first, that Soviet NSE in 1970 was approximately the sum of the reported “Defense” and “Science” appropriations in the USSR State budget–some 21 to 24 billion rubles. In 1975, Soviet NSE would amount to 22 to 28 billion by these methodologies. Second, it has been held that the share of NSE in Soviet GNP declined more or less steadily from 11 percent in 1955 to about 6.5 percent in 1970, and to 4 to 6 percent currently. In terms of the Soviet measure of national income (NMP)(Net Material Product), NSE accounted for roughly 15+ percent in 1955, and is now down to 6 to 8 percent. Third NSE claimed about 6 to 9 billion rubles or only about 20 percent of total Soviet durables output in 1970. Currently, the share would be down to 8 to 14 percent. Finally, the CIA argued that because the share of GNP devoted to NSE is small and has been declining, because the institutional rigidity of the Soviet system prohibits rapid and substantial shifts of resources from one use to another, and because any such transfer from military to civilian products and services would only accentuate the declining trend in the ratio of output to inputs, the burden of NSE on the economy is light. Hence, little if any, improvement in economic performance would result form reducing further the share of GNP devoted to NSE. Indeed, economic growth might be adversely affected by such a transfer.

[42] J. C. Masterman. The double-cross system in the war of 1939 to 1945. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1972. Print.